This clip is from a session at Second Order San Salvador, a five-day residential economics unconference hosted by Duncan McClements and me (Jan 7–11, 2027), graciously supported by Emergent Ventures and Jake Hamilton of Palestra. We’re interested in hosting similar events in the future and are currently considering possible follow-ups.

If you’re interested in more background, here’s the update I wrote to Tyler Cowen:

Hello Tyler. Second Order San Salvador went great.

The Pupusas were fresh; the talks were excellent; the brutalist church was indeed beautiful; we may have been able to set Bukele’s underling right on some boneheaded agricultural policy through Robin and Cremieux; and El Xolo served the best meal I had this year.

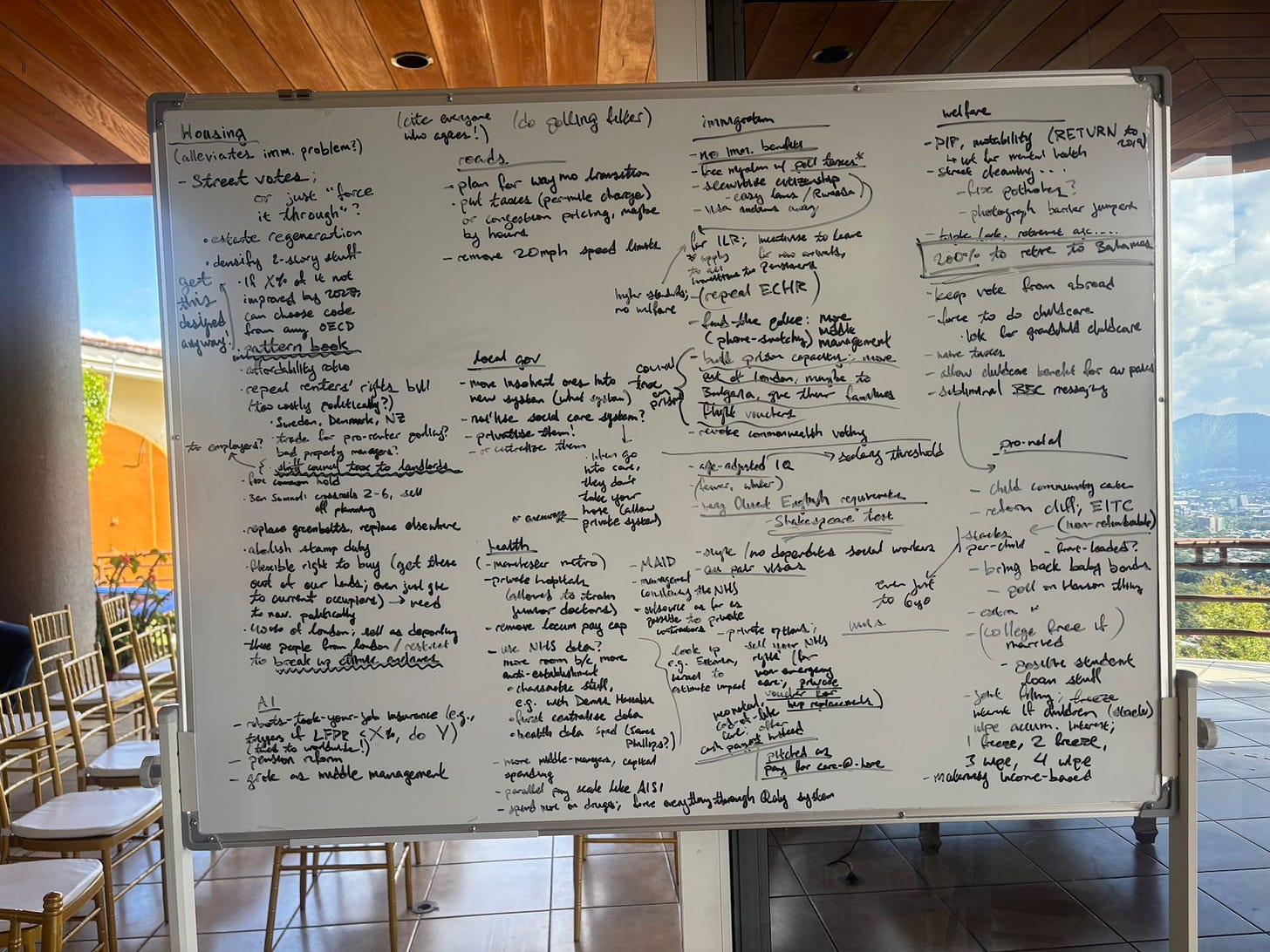

With Hackathon speed, we drafted a platform for Reform, who as of yet don’t have one despite being the highest-polling party in the UK. Housing was the keystone because the party has little to lose in terms of support in London, freeing them to defy the interest groups that would otherwise kibosh such efforts. Robin had some very fresh, political economy-compatible ideas for reorienting the welfare state around fertility, marketizing healthcare and education, and deregulating prediction markets. We have connections at Reform, and we’re trying to get them to take a look at it!

We ran a panel on the sociology of sexuality: What to make of the “smart teens don’t have sex” finding; why sexual markets don’t clear and what the sociological price controls are; Hanson on sex redistribution, transgenderism in Thailand, search costs, and multiple equilibria; why dating apps appear to have gotten worse; why married couples don’t have more sex (David Brooks didn’t have a satisfactory answer but we didn’t either), and the degree to which sexuality is socially mediated.

Other sessions ranged from Jones on optimal immigration policy, Latin American underperformance and solutions; a presentation from a local academic archaeologist Carlos Flores-Manzano (he had a very interesting take on the archaeological relationship between fungus eating and human sacrifice); Robin on aliens; Aria Babu on how to find a husband; and Robin again on his experience inside the U.S. national-security and research apparatus, the kinds of policy ideas they don’t like, and why.

Of course, Duncan and I learned some things from experience. We should have invited more people so we could hold multiple sessions at once (all told, we had 23 attendees, including 8 who were British and 2 Latin Americans). We should have filmed more sessions, because the ones we did film came out great. We should have tried harder to host Salvadoran government officials, though I expect that will be easier going forward. Most of all, we learned that we should have provided food, so people wouldn’t have had to go to separate restaurants and disrupt coordination by arriving back at divergent times—of course, there is a good reason why conferences tend not to handle meals like this. There is no such thing as an instantaneous lunch.1

But the most important thing I learned is that there should be more conferences. I thought organizing Second Order would be straightforward and yield excellent results, and such was the case. The ease of putting this on—though it’s a rather risky point to dwell on if I’m trying to highlight my own contributions—is simple enough to explain. Manifest Man, methinks, is actually quite competitive with Davos Man in many respects (if nothing else, if he were in charge, the world economy would grow at 6% a year!). Many things come easily when your ideology attracts intelligent, open‑minded people who are willing to take risks.

Credit is also due to our wonderful patrons who, instead of making us fill out 20 forms for kludgeocracy reasons, gave us a meeting within a weekend and a decision within 15 minutes; wired funds directly to my bank account; and require as recompense only a freewheeling, literary thank-you note. So thank you, Tyler, for revolutionizing philanthropy—even my university seems to be catching on—and for so much more. I’ll quote a bit of my opening speech:

The second person we should applaud is Tyler Cowen—the gray-eyed man of destiny. Not only because of the 5k he gave us for this conference, which is incredibly generous, but because of the very blatant extent to which our subculture owes him in general. All of what will happen here depended on an intellectual network he’s spent years building. Let us venerate this most illustrious of intellectual ancestors!

The EV grant was wonderful and covered the cost of filming the conference, the first fruits of which will be released imminently. But I must offer especially sincere thanks for starting all of this, for birthing Manifest Man like Athena from the head of Zeus and bringing him up. Duncan and I met at WIP’s Invisible College and got to know each other through the EV conference. Your efforts, very broadly considered, are what made this easy.

But if the easiness was easy to explain, its excellence was more subtle. Palpable, but subtle. On the last day at brunch, Hanson asked, “What made this unique?” because he couldn’t put his finger on it. As a group, we discussed the question.

Second Order felt meaningfully different from rationalist events, economics conferences, certainly from right-wing events. I think there were several reasons why: It was a hybrid of all those forms, and one more oriented towards normal prestige than the rationalist conferences that were the general mold. Brit Progress, Bukele, and Cremieux also helped to differentiate things. But none of that was satisfying to Hanson, who (unsurprisingly) was probably considering something more abstract. I think [REDACTED] said “the vibe was ‘what comes next’”; not just economics or the culture war, but wonkish, creative policy thinking on all fronts, with a rare emphasis on aesthetics and culture. I think that’s about right.

Where might that have come from?

My sense is that there’s real unmet demand, in a very general sense, for the GMU School brand. Should there be discussion groups? A “Schelling Point CMU”? Should there be biographical, perhaps documentary projects—say, a Five Lives of the George Mason School published by Tamara Winters, or a film made by Dutch avant-garde filmmaking collective Keeping It Real Art Critics?

These are, in any case, the questions and projects that increasingly occupy my attention.

Said Napoleon: “If you want to dine well, dine with Cambacérès; if you want to dine badly, dine with Lebrun; if you want to dine quickly, dine with me.”