For-profit government: The soul of Yarvin's thought

The definitive reading of the definitive figure.

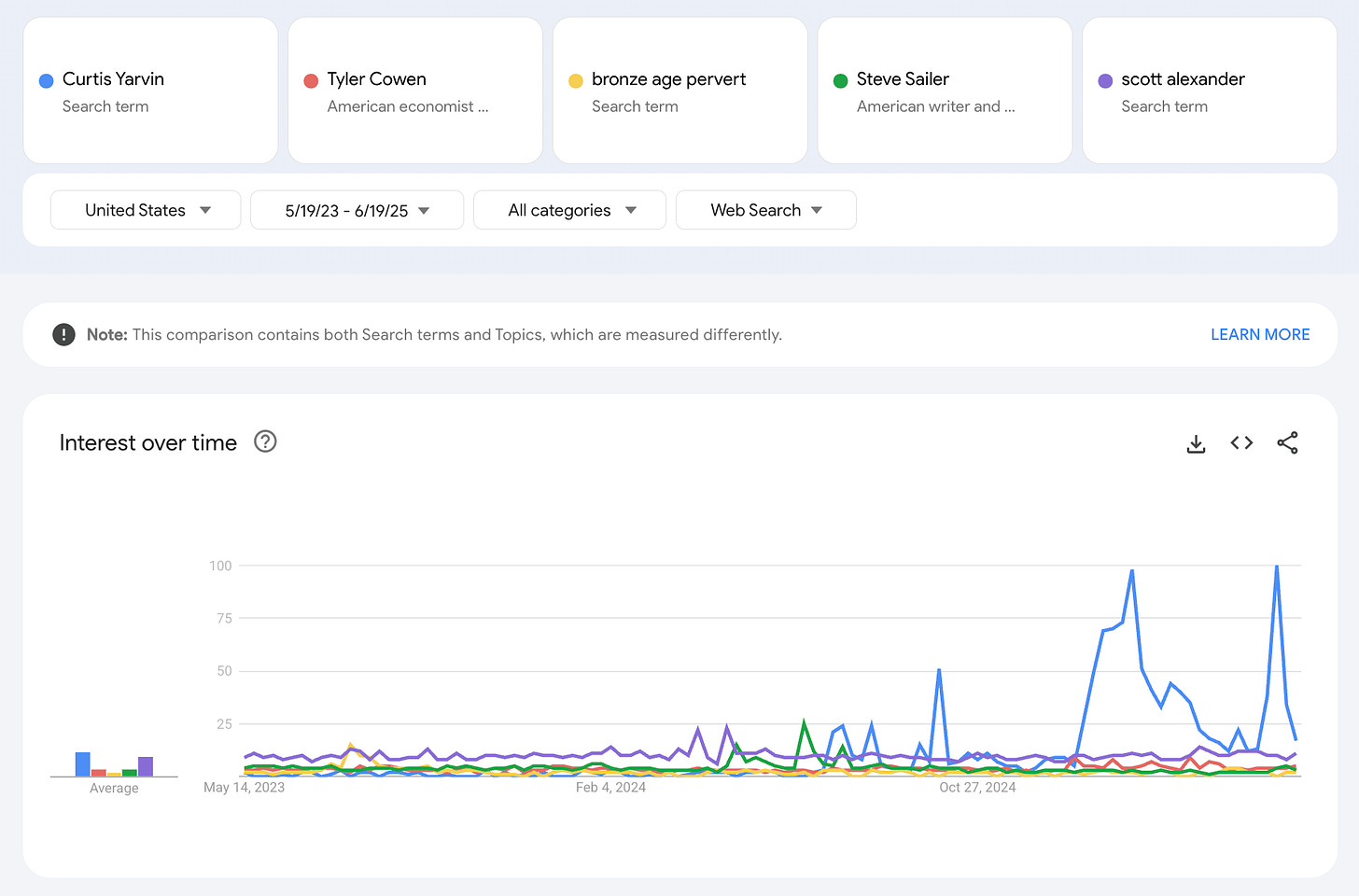

Internet writing is eating the world, and as the medium’s breakout mainstream-famous figure, Curtis Yarvin is the object of disproportionate attention. And this attention will presumably only intensify as Vance becomes more salient in the run-up to 2028.

The analytic depth of this engagement, though, is generally shallow. Did you like “Curtis Yarvin's Plot Against America”? I thought it was pretty good. I hope you liked the paragraph about me. I had wanted more; maybe next time.

Anyway, Ava Kofman understands Curtis Yarvin’s personality pretty well. Her article was sort of like Aristophanes‑on‑Socrates: spot‑on, even delightful as caricature, but fraught as explication. If you’ll let me get all Knoll’s Law, Kofman doesn't really understand Yarvin’s political theory and actually writes things that—as we’ll see—are factually incorrect about it.1

Both Kofman and Danielle Allen’s works would have been significantly more fun if they had engaged with Yarvin in a way that passed the Ideological Turing Test. But it’s not totally fair to fault them for it.

Unqualified Reservations may have a snazzy website these days, but Yarvin’s epigrammatic and conceptually dense prose—very atypical in our era—doesn’t help our clerisy, who will have limited attention to expend understanding a far-right blogger. What’s more, no secondary sources yet guide curious outsiders through the over 1 million words of Yarvin’s corpus (significantly more content than many of history’s big names). The canon remains mostly up for grabs.

I hope some eminent Yarvin expert gets around to writing the definitive exegesis soon.

A Concise Reading: What Yarvin Believes About the Problem of Politics

Mainstream academics who try to interpret Yarvin tend to be political theorists because the problems that Yarvin deals with are traditionally those of political theory. But unlike figures he’s often grouped with like Patrick Deneen, Yarvin is not actually grounded in the “political theory” tradition. He instead emerges from an alien discipline, that of economics, as part of the general trend of economics imperialism.

One could see Yarvin as a methodological cousin of mechanism design theorists like William Vickery, Paul Milgrom, and—dare I say—Glen Weyl. When Paul Milgrom designed the auction format that won him the Nobel Prize, he didn’t stop to wonder, “Is it just for the government to get so much money from auctioning off bits of the radio spectrum? Is money good?” Milgrom’s task is, of course, more modest and more tractable.

Curtis’s political thought is similar. He’s not concerned with who deserves to rule or what values they should uphold, per se. His goal is to design the structure that most reliably produces prosperity; his frame is, in some broad sense, utilitarian. Not the utilitarianism of Peter Singer or Holden Karnofsky, but the methodological utilitarianism that prevails when trying to do economics.

He picks an objective (prosperity or GDP), and, having inherited Rational Choice Theory from econ, attempts to design a system of incentives that implements the objective. Thus, Yarvin reduces the problem of politics to an alignment problem.

For-Profit Government, in Context

We’ve learned some things about running large organizations in the 250 years since Washington and Madison’s valiant right-wing coup against the disaster of the Articles of Confederation. In the late 18th century, the corporation was in its infancy. Now, corporate institutional architecture does almost everything of importance in our world. The number of effective organizations run like the American government, by contrast, is approximately zero, and Yarvinists think there is a reason for this—such experiments prove less effective and lose out to for-profit firms.

Does Apple have a constitution? No. So, how does it know what to do? It has a different model, a goal: to provide value for its shareholders, the fulfillment of which the CEO and board have personal stakes in.

What would a political system that internalizes 250 years of innovation in running large organizations look like?

Like many of the most successful organizations in the world, the neocameralist (the term Yarvin uses in his original blog2) state would sell shares on an American stock exchange, which would entitle shareholders to a portion of future dividends. The state would float its first shares on a public exchange to anyone who wants to buy them from the previous owners.3

Its shareholders would elect a board of directors, which would vote on a CEO who serves at the board's behest. Choosing political leaders is typically considered a hard problem, but in the private sector, it’s mostly a solved one—just get an executive search team. Call me crazy, but I think it’s actually possible this approach could manage to rival the renowned talent-spotting of American elections.

The mandate of this CEO is simple: maximize value for the shareholders; i.e., maximize market capitalization/GDP, which, though not perfectly correlated with human flourishing, is pretty close, and not that difficult to measure.

How does a government maximize GDP? Ask a mainstream economist, and they would say something like: maintain the rule of law and property rights, keep taxes at the Laffer curve optimum, and provide public goods effectively and efficiently. This government would not be incentivized to oppress or genocide any of its citizens, who are all its assets.

I think it’s easy to underestimate the beauty and promise of this idea.

You may have noticed that unlike approximately all modern political theory, Yarvin’s system has no grounding in the concept of rights. Don’t read too much into that: Yarvinists believe that our system would maintain human liberty far more assiduously than the current government does.

After all, though the vision of keeping government restrained with written constitutions was a noble experiment, we can now see that it is a failed one: the Alien & Sedition Acts, internment of Japanese, the Patriot Act4—courts didn’t hesitate to rubber-stamp them all. And fundamentally, any assembly that adopts the Bill of Rights can just as easily repeal or ignore it.

For a Yarvinist, limited government is a contradiction in terms. Instead, we must design a government with incentives to behave well.

Hayek taught us that the price system is an inhumanly effective aggregator of information. Coffee prices integrate immense amounts of information—weather, pests, shipping costs, and our cafe-side demand—into a single number. Under an NYSE-listed regime, the discount rate on its stock would do the same: serving as an unerringly reliable, ceaseless referendum on all policy.

Would the for-profit US ban, for example, gay marriage? I don’t think it would. Oppression shrinks the tax base and projects social instability; traders consider this risk when assigning value to the shares. The country’s directors would be prudent to reverse course before billions of dollars evaporate.

Would it assassinate its opponents? Random violence is a costly thing, and a CEO who engages in it invites a coup from the board. Arbitrarily seizing property sends the same message: your assets aren’t safe!

Rights, then, live inside the NPV: violate them and the stock reacts. They are protected not by fragile norms, but because defying them is tangibly, ruinously expensive.

A cold mechanism, perhaps, but far more credible than parchment promises that history demonstrates are abandoned when expedient.

I’ll be honest: As some sort of Chesterton's Fence conservative, I’m not absolutely sure I’d push the button to implement this in the US tomorrow. But I unambiguously support more experimentation—a for-profit government for Micronesia, say—and I think you all should too.

Neocameralism’s Place in Intellectual History

The concept of intellectual lineage takes up a lot of space in Yarvin’s thought. From How Dawkins Got Pwned—probably Yarvin’s finest essay:

In my opinion, the only sensible way to classify traditions—as with species—is by ancestral structure. While the existence of introgression and the absence of reproductive isolation makes it technically impossible to construct a precise cladogram of human traditional history, we can certainly produce sensible approximations.

So what is Yarvin’s place on the intellectual cladogram?

As a political thinker, he is descended chiefly from the Austrian School. Hans-Hermann Hoppe (though more of a crank than I’m comfortable with these days) argues in Democracy: The God That Failed that monarchy is better than democracy, since “no one ever washed a rented country.”5 But he also argued that “private law society” is preferable to either.

Yarvin dispensed with the chimeric “private law society” part of the argument, which itself can be seen as consonant with Austrian tradition: Since at least Murray Rothbard, Hoppe’s intellectual progenitor, there’s been a tendency to try to rehabilitate monopoly in radical libertarian economics. This culminated in 2014 with Peter Thiel’s Zero to One, which makes the case that natural monopoly is good. Yarvin made a more limited version of this case seven years earlier with Neocameralism: The state is a natural monopoly, and that doesn’t have to be a bad thing.

I’d be remiss not also to mention the influence of the Rationalist writers on Yarvin, whom I’d argue—though it’s somewhat radical—did basically come out of the Chicago Econ. GMU economics professor Robin Hanson studied epistemology at Chicago and econ at Price Theory outpost Caltech. It was he who “discovered” Eliezer Yudkowsky, with whom he co-founded the first Rationalist blog, Overcoming Bias.

The Rationalist movement has changed in various ways since, but its mores are still deeply influenced by this lineage: most notably their emphasis on empiricism (something Effective Altruism inherited), Rational Choice, and much of their terminology. As social theorists, the Rationalists unambiguously dwell within this paradigm.

As a political thinker, Robin Hanson is the most similar figure in modern intellectual life to Yarvin: Both devised and advocated remarkably original, econ-influenced systems of governance. Yarvin’s first public appearance as the author of Unqualified Reservations was in a debate with Hanson on the relative strength of their two systems: Yarvin’s neocameralism against Hanson’s rule-by-betting-markets.

At the time, there was no consensus as to who won. But I think we can now provisionally conclude that Yarvin did: after all, Hanson himself came around to the neocameralist position.

Internet Writing is Eating the World

As Kofman writes in her New Yorker profile of Yarvin—and it is an amusing passage:

The eternal political problems of legitimacy, accountability, and succession would be solved by a secret board with the power to select and recall the otherwise all-powerful C.E.O. of each sovereign corporation, or SovCorp. (How the board itself would be selected is unclear, but Yarvin has suggested that airline pilots—“a fraternity of intelligent, practical, and careful people who are already trusted on a regular basis with the lives of others. What’s not to like?”—could manage the transition between regimes.)

But Yarvin just totally spells this out in a way totally unrelated to aviation, as in Against Political Freedom:

To a neocameralist, a state is a business which owns a country. A state should be managed, like any other large business, by dividing logical ownership into negotiable shares, each of which yields a precise fraction of the state’s profit. (A well-run state is very profitable.) Each share has one vote, and the shareholders elect a board, which hires and fires managers.

This happens a lot. At my Great Books-flavored right-wing summer program, we recently hosted a guest speaker from a nearby university. With a nifty slideshow, she expounded on the ideas of three contemporary thinkers: Patrick Deneen, Danielle Allen, and Curtis Yarvin.

Yarvin’s slide? Two quotes on monarchy from his recent interview with NYT, and two quotes from Unqualified Reservations, on the subject of race.6

And that was just the first time! At Hertog, there are speakers around three times a week, and they bring up Yarvin like a quarter of the time—negatively, of course. Jonah Goldberg, for instance, got up and noted, after saying something grouping Yarvin and Deneen, “Monarchy, that’s not a new idea, it’s actually a very old idea.” Neocameralism—as I hope I’ve made clear—is something quite novel.

The intellectual level of this engagement is super low compared with the criticism of Yarvin you could find on, say, 4Chan. I think that’s a problem.

There’s a structural reason all of these generally intelligent people just can’t get it. Yarvin’s paradigm—interspersed between ≈600 essays that are 1/4 block quote and 1/12 ironic—is just different. From econ he inherits Rational Choice, methodological individualism, and, at least implicitly, preference-satisfaction utilitarianism (if only later to internalize various critiques of it). I don’t know that much about Danielle Allen, but I think it’s quite possible she never took an economics class.

I am reminded of a line from Cowen on Dwarkesh:

Regarding the internet writing mode of thinking, I would like to see more economists and research scientists raised on it, but the number may be higher than we think… It’s a very powerful new mode of thought, [and] it’s not sufficiently recognized as something like a new field or discipline, but that’s what it is.

Cowen described this enterprise further with Aashish Reddy:

[In internet writing,] you use an informal voice. You try to get to the point quickly. You might link to things, but you’re not so obsessed with origins of ideas. You bring together reasons from different perspectives and try to synthesise them. And there’s a deliberate disregarding of what we used to call “high culture” and “low culture” arguments. And there’s a tendency to be prolific, and maybe do many short things compared to the world of books. Off the top of my head, that’s how I would characterise Internet writing—other than of course, it’s on the internet. You give it away for free, usually—not always, but it’s sort of for free.

Of course, Yarvinists have bigger gripes with the Cathedral than its difficulty with understanding internet writing. But should there be Internet Intellectual History? Ought it do for blogs, listservs, and forums what Cambridge contextualism did for 17th‑century pamphlets? What would its canon be—which of Yarvin’s essays?

Should academics be allowed to cite altmetrics alongside citation indexes in tenure dossiers? Should there be “journals” of blogs? Should every department be like GMU Econ? Should Yale hire me?

I’m not sure, but I think these are some of the questions people should be asking. Because Yarvin will probably not be the last to popularize a new ideology over the internet. On the contrary, he’ll in all likelihood be seen as only the first.

Am I the only one who remembers Scott Alexander offering a bounty to anyone who could find a lie in the mainstream media? I think I found one!

The two central essays for understanding Yarvin’s political thought are “The Magic of Symmetric Sovereignty” and “Against Political Freedom”.

Not something I actually have an opinion on, tbh.

Whatever you think of him, doing this much to explicate why “monarchy” is so common historically affords Hoppe some place in some canon. I tentatively plan to be at PFS next year.

These two quotes also appear on Yarvin’s Wikipedia page.

Not to be a pedant but Apple does on fact have a constitution - its articles of incorporation. Albeit that is not the source of its value

For a more serious and nuanced treatment of the idea of for-profit government I’d recommend reading The Proprietary State. The idea of for-profit governance isn’t new at all and has been called “proprietary governance” since the seventeenth century.

Constitutions (articles of incorporation) are essential parts of incentive systems to align the interests of politicians (managers) with voters (shareholders). Yarvin’s idea of having no constitutional constraints on the managers of proprietary governments is based on the false notion that constitutions will always be ineffective. The U.S. constitution might not always have been effective, but that doesn’t mean constitutions are worthless in principle. It takes a combination of institutions for them to work well. When they’re carefully designed, they’re mostly effective. If they weren’t, every elected leader could have abolished democracy immediately after being elected.